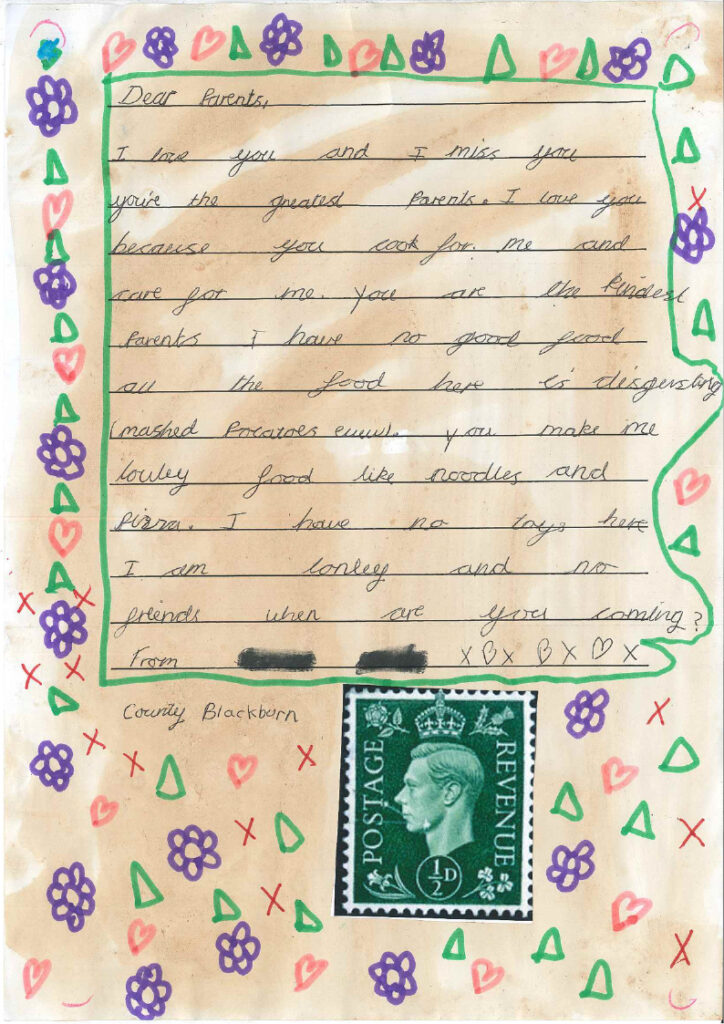

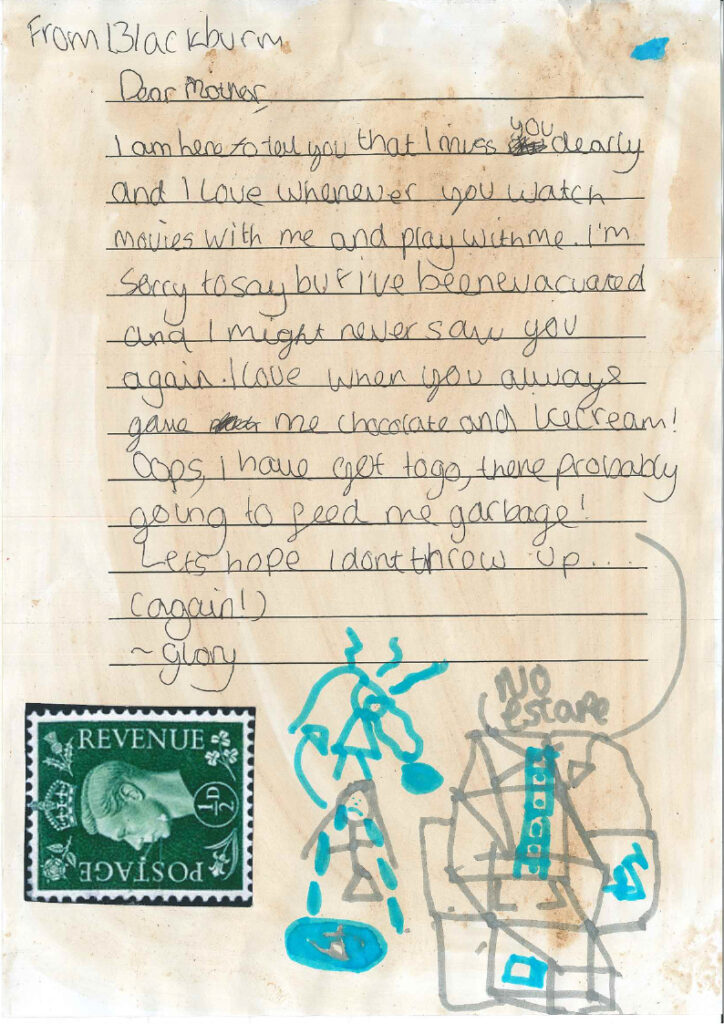

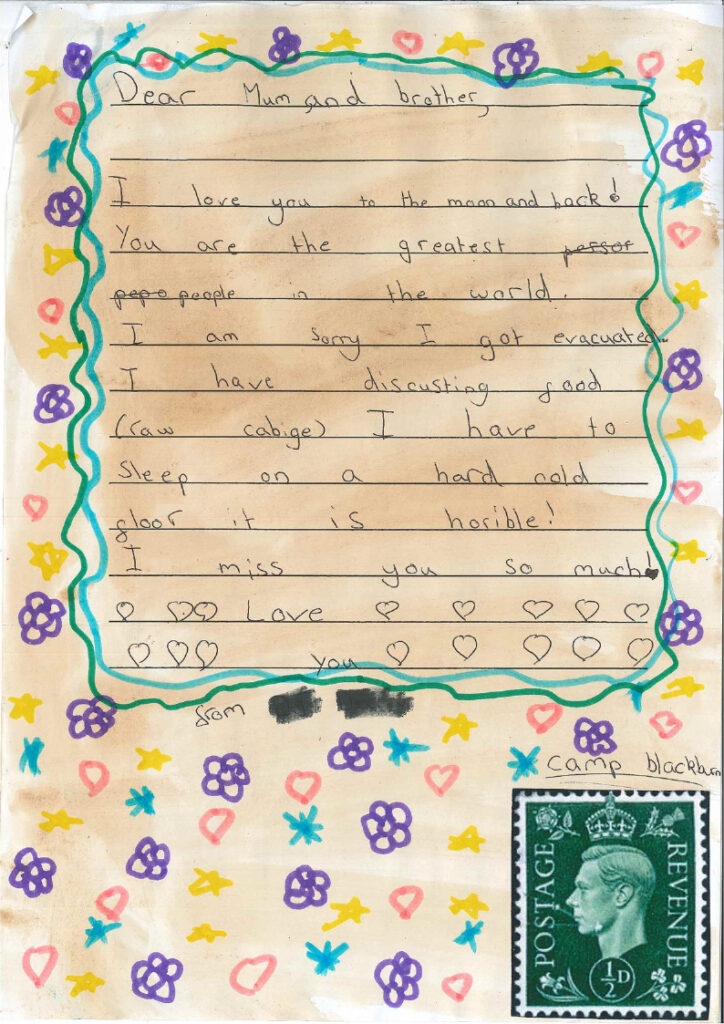

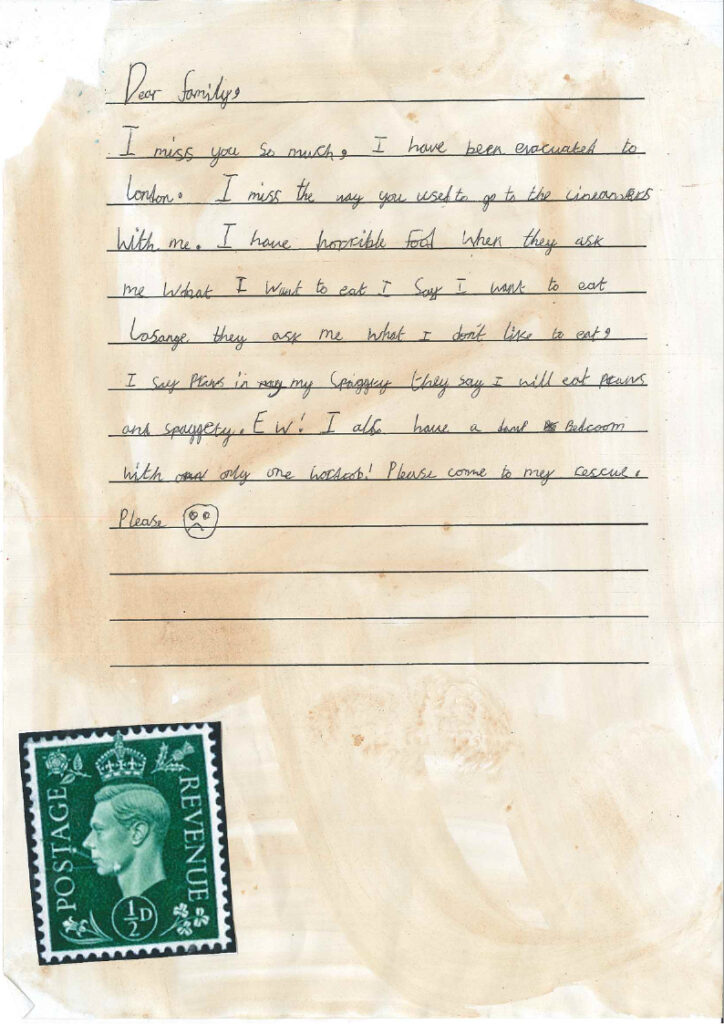

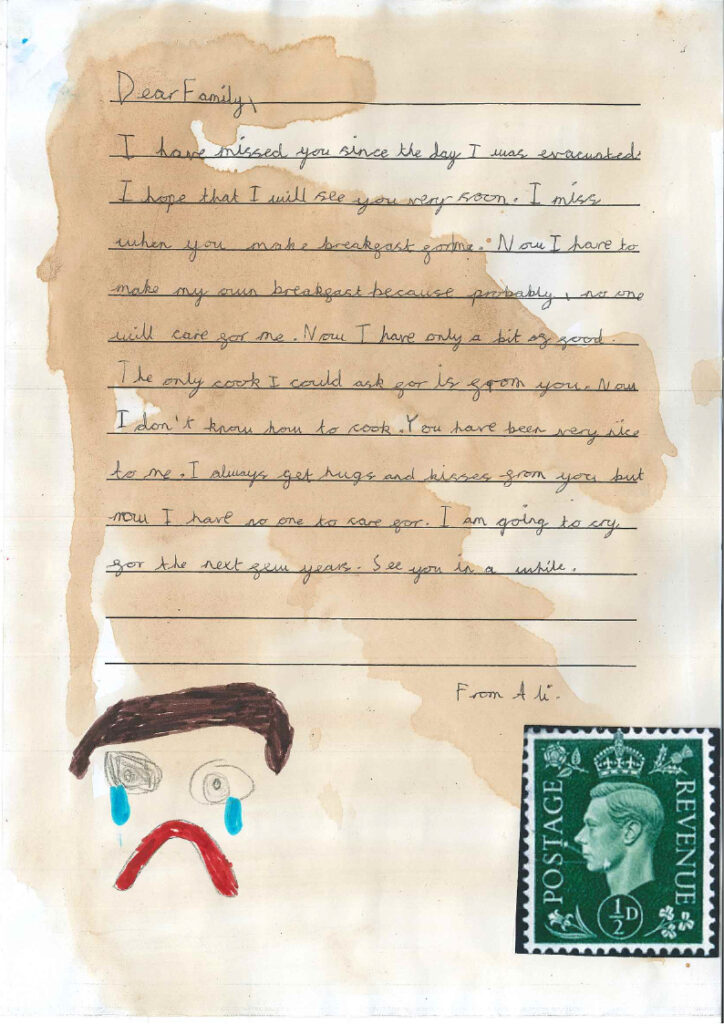

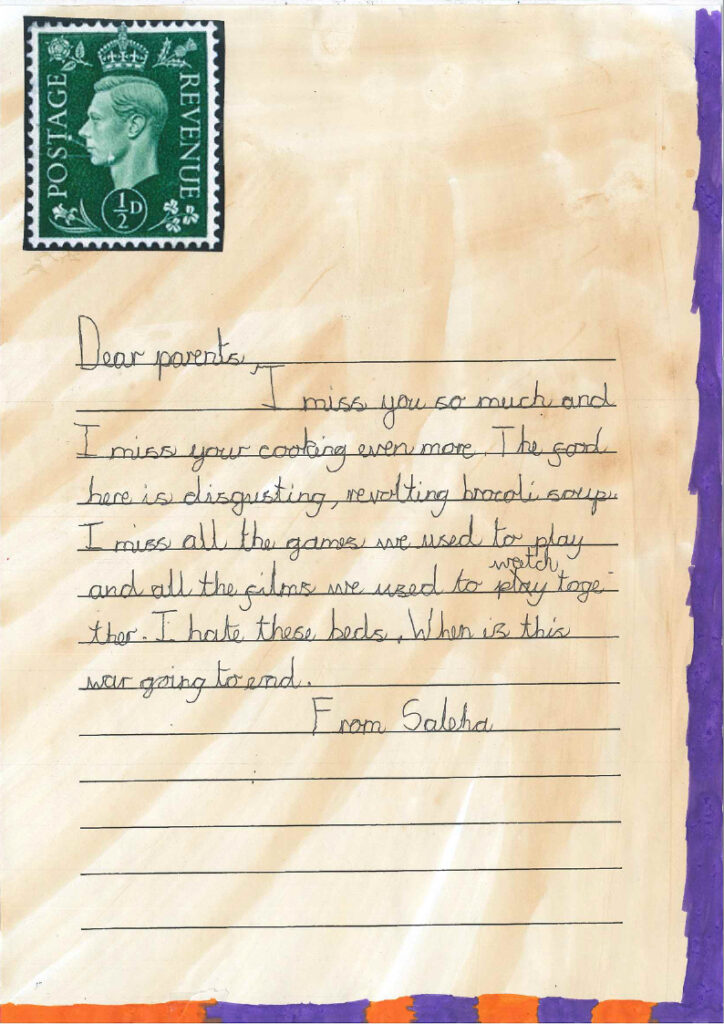

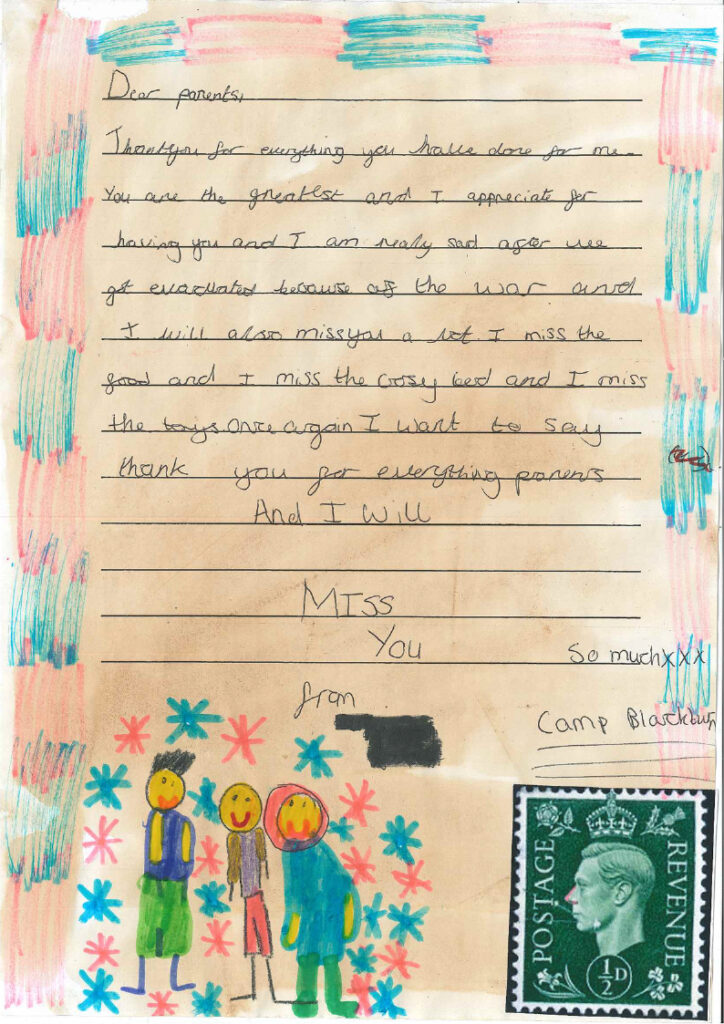

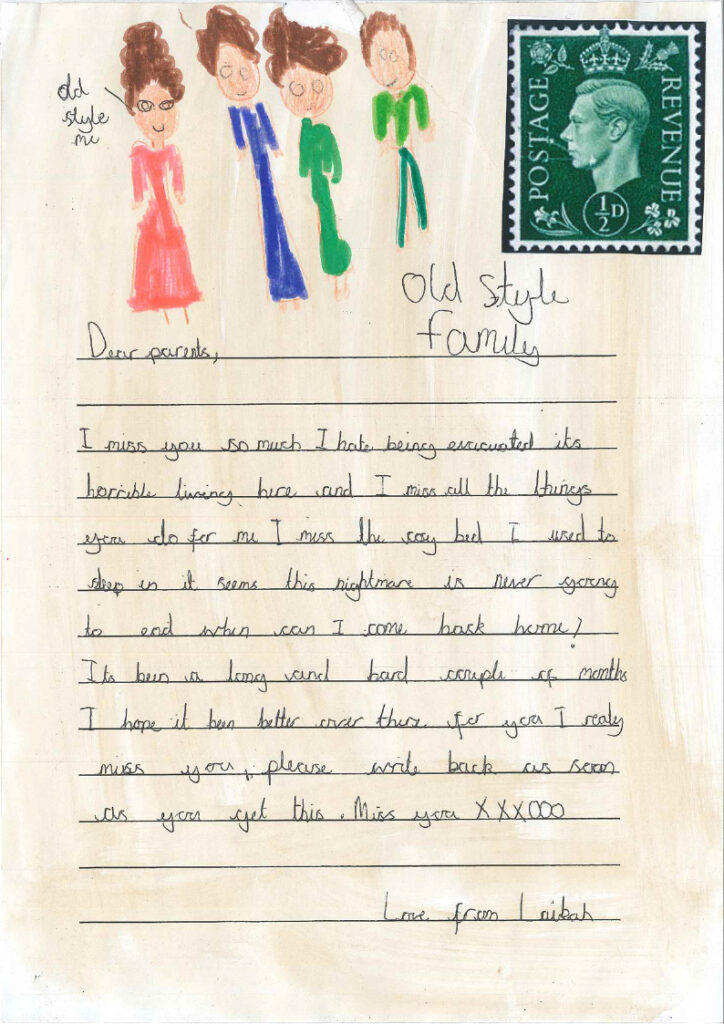

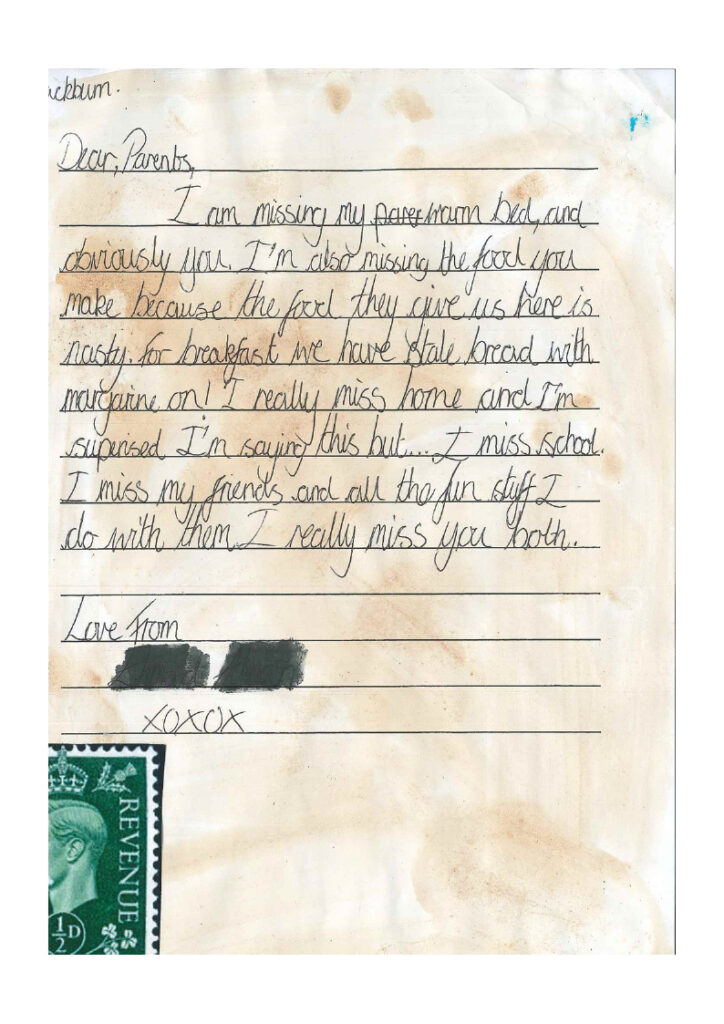

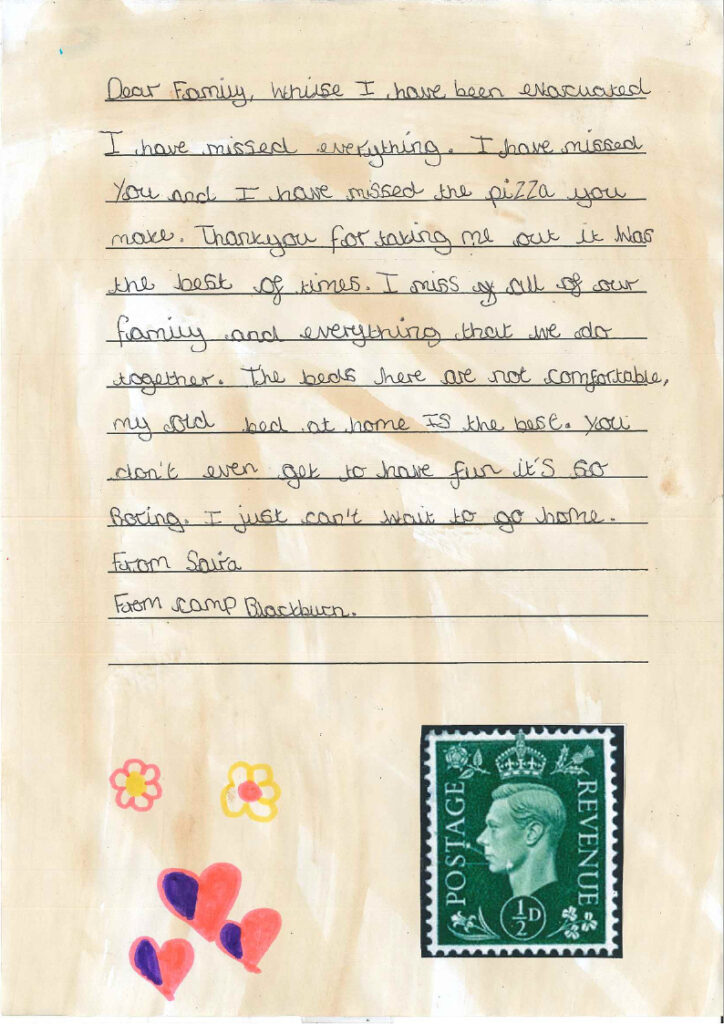

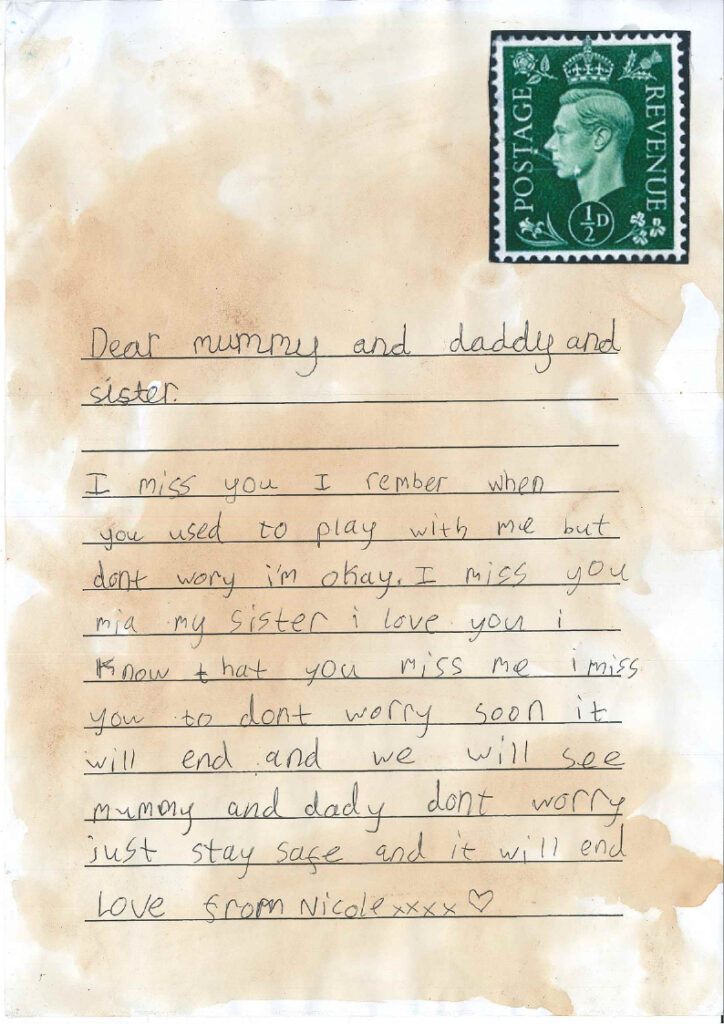

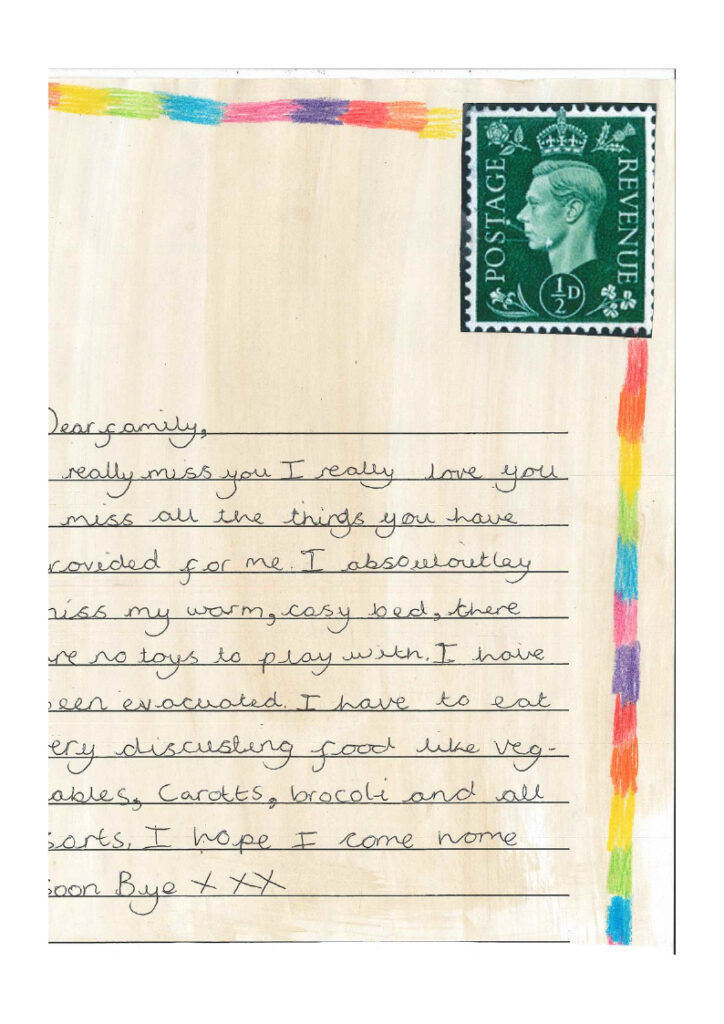

Children from Blackburn Children’s University were asked to imagine what it might be like to be an evacuee during WWII and were asked to write letters home to their parents. These are some of their letters.

Children’s University Writing Competition: A ‘Wartime Childhood’ Christmas

In November 2019, children from Blackburn Children’s University took part in an event called ‘ A Wartime Childhood’ run by staff and students from the School of Art and Society. As Christmas 2019 approached, the children were asked to write stories imagining how it might feel to be a child during war time.

Here are the entries from the winners and runners-up.

A Wartime Childhood, by Aamina (year one)

I will be worried because they will shoot the gun at me. I will not see my daddy because he will be in the world war. I am upset because I am missing daddy. I want Santa to bring daddy home wrapped as a present so me and my sister can open it. This will make me happy.

I am scared daddy will never return. He might get shot in the world war.

A Wartime Christmas story, by Shayaan (year two)

Hello! I am Adam, and I lived at the time when the Second World War was taking place. My father had been sent off to join the troops and my mother quietly ushered me and my little sister, Lily, along with the rest of the children, to a peaceful countryside to keep us all safe from the German soldiers. I made plenty of friends, all from different cities and towns in Britain. When December has arrived, my friends and I were so excited. We made our very own advent calendar (because we couldn’t go to the shops) and started to count down the days to Christmas Eve and Christmas day itself.

Soon enough, Christmas Eve had approached. All the children living with me were very excited for Santa to come and shower our Christmas tree with presents. Very carefully, we started taking out paints and bits of newspapers and started making paper chains to decorate the room. Of course it was hard work making the chains. You had to cut the newspaper into strips, paint them in different colours, wait for them to dry and then put glue on them to stick (or link) together!

After we decorate everything, we play board games. I always lose, but that’s how I learn! However, I am really good at Scrabble and making different words and getting double and triple points for each letter! Yay me! ?

It was finally getting towards 8 o’clock, and it was time for bed. Silently, I put on my pyjamas and snuggled in my roughly made bed with my 5 year old sister Lily.

Then Santa had come!

It was a MIRACLE!

A Christmas in the Countryside, by Afiya (year three)

The sharp sound of guns rang in Lewis’ and Zara’s ears every single day. They were stuck in the middle of a war and their father was fighting on the battle front. It was just Mother and them but it was becoming unbearable. Recently, there had been many bombings near their house and the street in front of them was completely destroyed. The children were unsafe living in the city so Mother made the hard decision to send them away to live in some peace – now they were evacuees. They had to pack away their belongings and catch the next train. The journey was long and boring because they missed their mother.

When the train stopped. Lewis and Zara stared at the fields and trees in amazement. Then a lady came to them and glared at their tired faces. She silently led them to their new house which seemed to have a horrible smell. Each room was filled with pink, hurting your eyes. As Lewis gazed at her, she introduced herself as Charlotte and ordered them to their room. It was quite small with only one bed and an old chest of drawers. Zara sighed as she started to unpack her clothes and Lewis tried his best to be positive. But what they really wanted was Mother and Father.

In the windows of the other houses, the children saw Christmas paper chains and they could hear Christmas carols. Charlotte didn’t have much up but the children got creative in their own room, making stars and snowflakes. The days passed slowly but soon it was Christmas Eve! Zara woke up excitedly and scared Lewis with her shouting. Charlotte stomped upstairs telling them breakfast was ready. The day passed like the others and it was quickly time for bed. They both got changed and tried their hardest to sleep but Zara could hear someone crying. Fed up of following rules, she decided to investigate. She peeped inside the kitchen and found Charlotte on the floor crying with a baking bowl in her hand. Zara called Lewis to join her and they both went up to Charlotte, trying to comfort her. Charlotte told them about how she was trying to bake a cake as a Christmas present but there wasn’t enough sugar. Baking also reminded her of her husband, John, who died in the war. Lewis and Zara had an idea.

They told Charlotte of their plans to ask the street for ingredients and she gave them a hug. They wrapped up and went outside on their mission. Lewis knocked on each door and Zara explained their plan. Everyone loved it and they were happy to help.

The next day was Christmas and Charlotte was up early, baking the special Christmas cake. The house smelt delightful. She carried it to the local village hall where the entire town was waiting. Everyone sang some carols and then it was time to eat. Charlotte was nervous but everyone loved it! Lewis and Zara were happy that their plan worked and they had an amazing Christmas in their new home.

1944 WWII Wartime Childhood, by Cheng (year four)

I was woken up by bombs and sirens everywhere in London. I had four gas masks for my father, mother, my little brother and also myself. We got outside and hid underground and we also closed the lights in our house and underground. We had lamps with us and also a bucket. We had to stay underground for two weeks. I heard screams, bullets being shot out of guns and it was a disgraceful sight. My mum opened the lamp and underground it had four chairs. Behind the chairs was a wooden door so I opened it and there was a shop. In that shop were my friends. They were Lin, Aliyah and their mum and dad. Me and Sammy were so excited to see Lin and Aliyah and we said ‘Hello’ to each other. However I saw something behind them and they were making paper chains using scraps of painted newspaper and other friends making pictures on paper. We helped them make the longest paper chains. We kept making more and more until there were no sheets.

After that, it was the last day and it was time to get out of underground. We hugged each other and got out. We waved goodbye and went home.

This is the best day ever!

My Christmas Story, by Mehek (year 6)

BANG! BANG! That was the sound of deathly shooting. Charlie and James were petrified with fear. Their mother, Emily, was also terrified. The place they lived in, London, was filled with smoke and pollution. It was a cold stormy night and their father had gone to fight on the front lines. Outside the rain lashed and pelted down.

Just then there was a knock on the front door. ‘I wonder who it is,’ pondered Mother. As she opened the front door, there was a man dressed in a black suit and hat. Whilst Charlie and James were doing their homework, they stopped for a moment and heard Mother talking. There was a lot of shouting and arguing. For a split second, they thought it was Father. But it wasn’t.

It was the man who came to take the children to keep them safe. The children had heard the big girls and boys talk about it. KNOCK! KNOCK! They opened the bedroom door. The man said, ‘Get your things ready, you’re going to go.’ Without thinking, the two boys got their bags ready. It was quite a difficult thing to say goodbye to their beloved mother but they followed orders and made their way towards the train. As they entered inside the train, they looked around and wondered where they were going.

After a long 2 hour journey they had arrived at their new house. They were now evacuees. They both felt a bit homesick because they missed their mother. When they met their new mother, Anne, they felt at home because it reminded them of their old mother. It was just a few days till it was Christmas. At that time, there were no shops because everyone was out at war. On Christmas Eve, the two boys were making Christmas decorations. They also started making their Christmas dinner. They couldn’t wait for tomorrow. Time had gone so quick.

The next day it was Christmas day! When Charlie woke up, he screamed with happiness and joy. James was excited too. As soon as they came out of the bathroom, they quickly ran downstairs and found presents under the Christmas tree. They went to the kitchen and found Anne making a cake. In the corner of her eye, she saw the two boys spying on her. ‘What are you doing?,’ they questioned. She said she was making something for later on. So eager to find out what it was, when Anne had left the room, they went to see what it was. Just then Anne came back in the room and found James and Charlie secretly spying on what she had made. They saw Anne and ran back to their seats and finished their breakfast. A few hours later, they were all dressed and had their scrumptious dinner. Then the cake had arrived. It was made from grated carrot and breadcrumbs. After eating, it was present time. All the gifts were homemade. Charlie and James gave Anne a special personalised rug and she had tears filled with happiness. Charlie got a homemade collection of jungle animals and James got a spinning top and a board game. It was their Christmas ever.

Lest We Forget: Family History, Memorabilia, and World War II Part 3

Dr. Stephen Tate

July 2020

Welcome to the third post on the blog, Lest We Forget. As part of the WWII East Lancashire Childhoods project the blog aims to examine how family memorabilia combined with shared recollections can help foster a better understanding of the generations associated with World War Two.

In this latest blog I want to examine the idea of oral history. The advantages and some of the pitfalls associated with this method of historical enquiry – a method that might be best suited to the sort of family reminiscences that this World War Two anniversary lends itself to. There’s a sense that oral history, history written or recorded as evidence gathered from a living person, perhaps a family member, can provide us with a direct route to the past, unadorned and unembellished. A means of extending the historical record – what we know of the past – to include the ordinary man and woman, perhaps our elderly relatives and their memories of wartime, or of their parents’ memories as recounted to them many years earlier.

At its most basic, oral history, in terms of this wider heritage project, can be described as talking to elderly relatives about parts of their lives that might otherwise go unrecorded. It involves recording, in some way, their first-hand recollections.

For some historians oral history, the spoken word, is a poor substitute for official records and written sources. They argue that spoken reminiscences leave too much open to doubt and to speculation, too much rests on the whim of the speaker, the person being interviewed, as to what they see fit to reveal and what they wish to remain unsaid. Spoken reminiscences can lack a sense of precision. Memory itself can be elusive and limited, open to forgetfulness and partiality. The order of events can become blurred. There are gaps. And oral history can only take us a relatively short distance into the past. It depends on what people can actually remember accurately!

But proponents of oral history as a means of understanding the past argue that it can deliver a sense of freshness. It assumes that everyone’s memory is valuable, however humble the person speaking or being interviewed might feel. It can certainly expand and extend the range of ‘voices’ from the past, opening the door to those outside elite circles, those living what might be seen as more ‘ordinary’ lives. And the argument that oral history can lack precision is often compensated by the element of emotion and detail that personal memories can deliver. At its best, oral history can deliver powerful insights, it can speak of the lived experience, it can deliver a sense of immediacy, and it can provide colour and drama!

‘Doing’ oral history sometimes involves quite sophisticated techniques, but it can also prove accessible to all. It can deliver a democratic feel to the study of the recent past. Everyone’s testimony can have a value. That is particularly true when, in our case, we might be interested in simple domestic routines associated with life in wartime Britain. The sort of detail that just might not be recorded anywhere else!

One thing to bear in mind if we embark on our own version of an oral history project, is that in recording wartime or as-near-wartime reminiscences as feasible, our presence as an interviewer is bound to affect the person being interviewed. It will influence what they recall and the manner in which they recall it, especially if being led by our questions. Even if we ask no questions and just listen, we are playing a part in the process. As one historian wrote, “the voice of the past is inescapably the voice of the present too”. The memories we are presented with have been filtered through other experiences and in a search for a sense of the past, as in some forensic exercise, we risk ‘contaminating’ the evidence. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try!

But let’s think of a few rules. Presuming we are looking at family members speaking amongst themselves, it is still important to tell the person you are interviewing what your purpose is – what you will be doing with the interview, whether it be written down or recorded. Will you be circulating it among other family members? Or outside the family? If they are to go beyond the family, you need to know if the interviewee is happy to have their name linked to their reminiscences or whether they would prefer a form of anonymity, say, with just their age and perhaps initials to identify the speaker. We must maintain an air of respect, too, in how we deal with the interview process and the end product. It is important to prepare for the interview, or series of interviews. What is it you want to discover? Have starter questions in mind. Decide how much you are prepared to intervene to guide the conversation if things slow down. Consider a few prompts in terms of events, locations or the names of other family members from the interviewee’s generation that might guide the course of the chat. Be prepared to be flexible. Think of the times on TV chat shows when someone being interviewed has started to discuss a really interesting point only to be annoyingly interrupted by the host (all too keen to hear their own voice) and the moment has been lost. Sometimes it’s good just to go with the flow . . .

A good example of oral history in practice can be found on this heritage website (‘When the lights came back on in Blackburn’). Stephen Irwin, Education Officer at Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery, interviewed Richard Croasdale who was a young child when war broke out. The questions Stephen asked in a telephone conversation had been prompted by children from our area, including Blackburn Children’s University, intrigued by the stories on this website. The details Richard reveals are fascinating, and I was particularly taken with the childhood rhyme for skipping! The ordinary parts of life all too easily lost to the record.

On a personal note, I regret not having engaged in that sort of oral history exercise in my father’s lifetime . . .

On the last web posting I said I would continue my late father’s story, following his ‘archive’ in chronological fashion, from the surrender of British forces in Hong Kong in December, 1941, where he was posted in the Royal Artillery, and the means of families finding word of those missing in the pandemonium of war. If you recall, I went out of sequence in the last blog and wrote about a powerful, recurring image of my father’s end to captivity after three-and-a-half years, prompted by the letter home that he wrote to his parents mentioning Lancashire songstress Gracie Fields entertaining the troops in Manila in the Philippines.

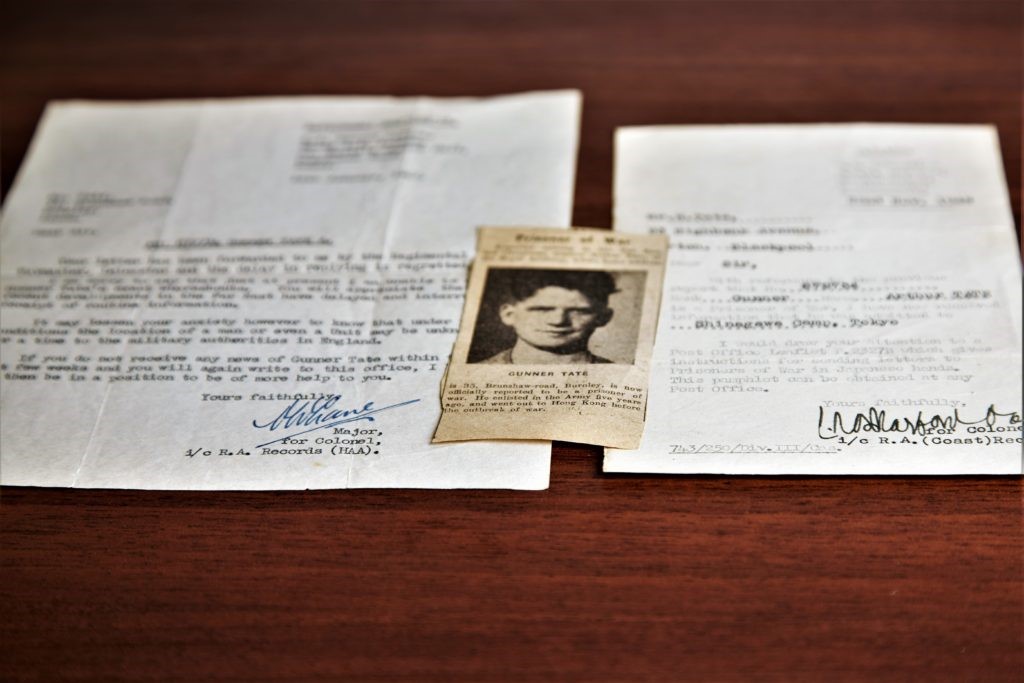

I want to return to the months following the fall of Hong Kong to the Japanese army in late December, 1941, and consider the trauma my father’s family must have experienced on the Home Front. The mood is captured in a handful of newspaper clippings and official letters. The first, of January, 1942, a tiny news-cutting from a Burnley newspaper, carries under a small headline, ‘MISSING’, the fact that ‘Gunner Arthur Tate’, who had enlisted aged 15, had been ‘posted missing’ after the surrender of Hong Kong. The nine lines of print are accompanied by a head-and-shoulders pre-hostilities portrait photograph of an incredibly young-looking and proud teenager in uniform. In the same month, his Burnley-based father and step-mother received an official typed letter from the Royal Artillery in Rugby. It was clearly in response to an earlier enquiry seeking news of their son. The letter informs the couple that, ‘I am sorry to say that just at present I am unable to state Gunner Tate’s exact whereabouts. You will appreciate that the recent developments in the Far East have delayed and interrupted the receipt of routine information. It may lessen your anxiety however to know that under present conditions the location of a man or even a Unit may be unknown for a time to the military authorities in England. If you do not receive any news of Gunner Tate within the next few weeks and you will write again to this office, I hope I may then be in a position to be of more help to you’.

It is clearly a standardised letter, the sort being received at thousands of homes across Britain as the war began to take its toll. Some six months later, in July, 1942, the same Burnley newspaper among its reports of local men missing in action from various theatres of war, carries equally brief news of Gunner Tate, announcing he, ‘is now officially reported to be a prisoner of war’. That, too, is accompanied by a photograph but, intriguingly, one different to the one printed earlier in the year.

There is a postcard among my father’s ‘archive’, unfortunately undated, written in pencil, faded by the years, from ‘Hong Kong Prisoner of War Camp’. In half-a-dozen lines my father writes to his parents, ‘I am quite well and in good health and I hope you are the same. We are being well treated so please don’t worry . . . hoping we will meet again very soon’. Prisoners were allowed to write only brief remarks, approved by their captors. How long it had taken the card to reach Burnley is not known, but presumably it was the first word of his whereabouts, of his survival, since the colony fell months earlier. The mood of his family when the card arrived can only be imagined . . .

In the next blog I want to concentrate on my father’s wartime ‘archive’, and consider the means of staying in touch during the long years of captivity.

I will close this blog by once again using one of my favourite quotes on the nature of History and this time it’s from a book on the sporting past, although the context is not really relevant. Here the author cautions against present-day readers imposing their own ideas, their own world view, on individuals from the past, or of attempting to explain their actions merely in terms of our own experiences. It’s quite a lengthy extract, but it is central to a reasoned understanding of those who have gone before.

“It is worth stepping back from the discipline and its attendant debates to remember that what we call ‘history’ or ‘the past’ was the present for other people. An appreciation of this simple fact is useful when faced with debates about the nature of history. The people who lived through what we are studying were not thinking of themselves in the historical terms that we use for them, but were simply getting on with their lives: fighting their wars, having their families, worshipping their gods, working in their fields, or whatever. Keep this in mind whenever you come across historians using shorthand terms such as ‘between the wars’ or ‘before the industrial revolution’, and remember that the people who lived then could not have known what they were between or before. The period we now call ‘medieval’ or ‘the middle ages’ was, for the people living through it, nothing to do with the middle of anything: to them, each day was the present. Remembering this can also help you to avoid anachronistic judgements about past people’s behaviour, beliefs, or motives. Burning women accused of witchcraft, voting for a dictator, or basing an entire economy on a single crop may all strike us as foolish things for people in the past to have done: but those acts must have made sense or been viable options for the people who did them, and to criticise them only in the light of later evidence or opinions does not make for good history.” – Martin Polley, Sports History. A Practical Guide (Palgrave Macmillan), 2007, p.6.