Dr Stephen Tate

December, 2020

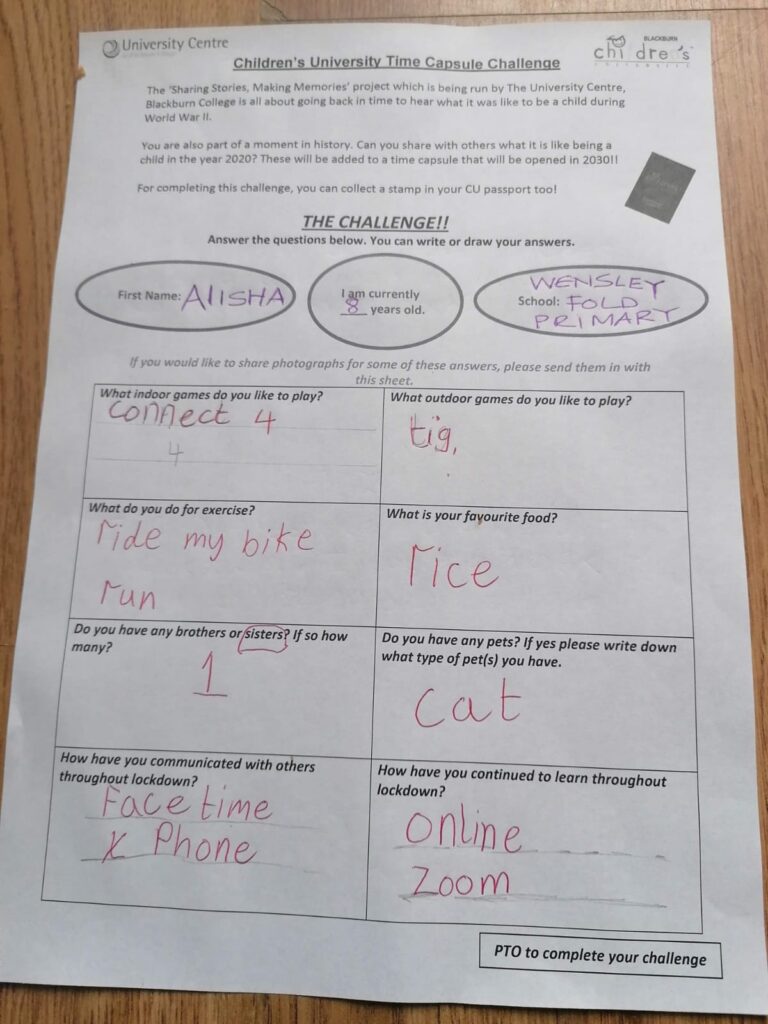

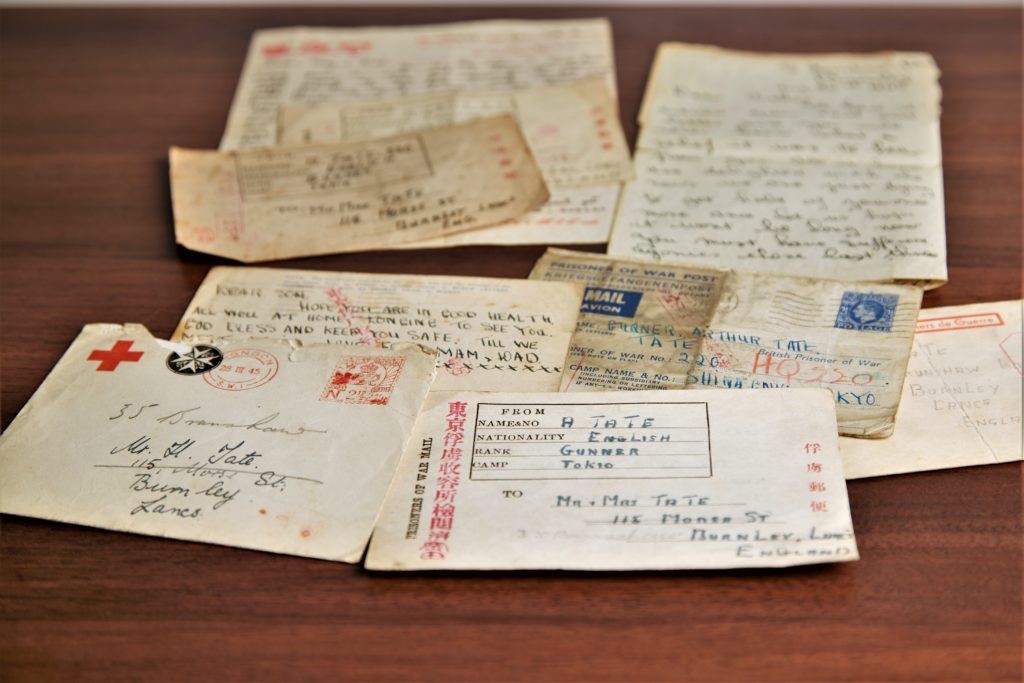

In what is the fifth and final blog in this series of posts I want to bring a sense of completion to my review of my late father, Arthur Tate’s ‘archive’ of material associated with his time as a prisoner of war in the Far East during World War Two.

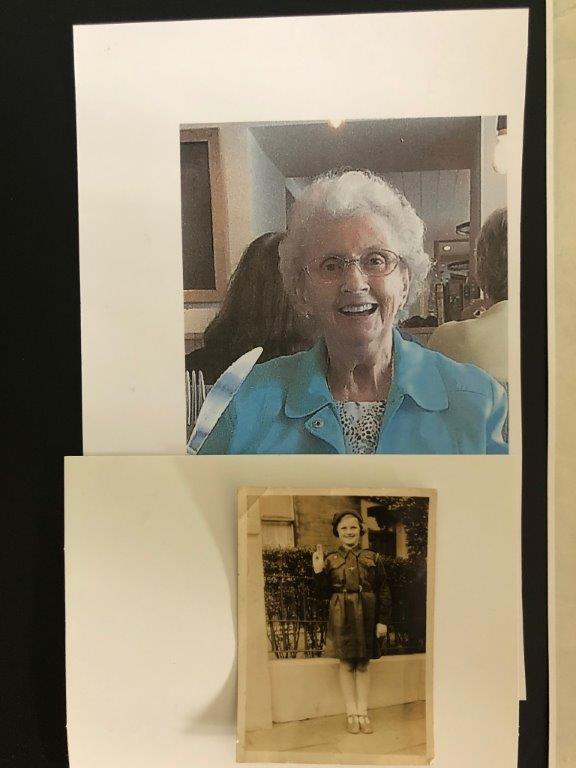

Throughout these posts I have touched on a theme of missed opportunities on my part to fully engage with my father regarding the full meaning and context of the material he had saved for posterity – often against the odds and at great difficulty. There are gaps in my understanding that cannot now be filled, and I have consistently urged readers to take whatever opportunity presents itself to open a dialogue with older generations. They often have a wealth of knowledge and experience about the past which risks being lost to the record unless we go to the trouble of talking, listening and storing their reminiscences and insights.

Many have stories to tell of significant episodes in the history of this country that they experienced close up or from afar. But even the everyday and the apparently mundane aspects of daily life can illuminate the past in ways that ‘big history’, the narrative of conflict, of the movers and shakers of society, of institutions and organisations cannot.

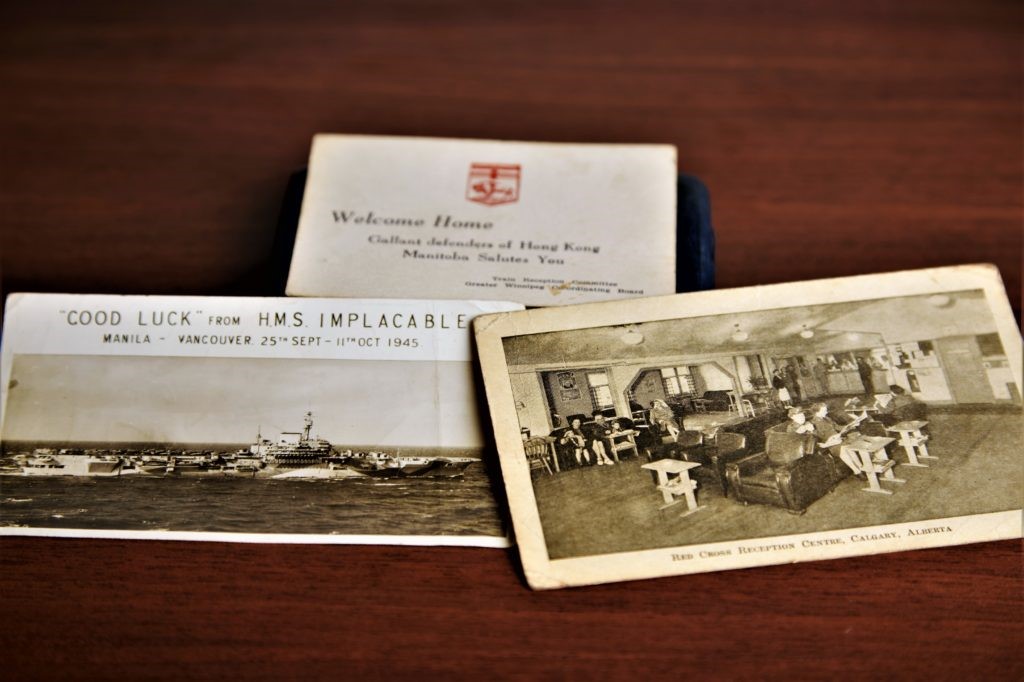

With that in mind, I turn to one of the photographs at the end of this piece that features three items – two postcards and a greetings card. One of them is a postcard of the British aircraft carrier, HMS Implacable, which was refitted at the end of hostilities in World War II in order to play a part in the repatriation of British, Canadian and American prisoners of war. The ship’s hangars had been converted in Sydney in order to accommodate the extra passengers. My father and many hundreds of fellow camp survivors from across Asia were transported on Implacable across the Pacific, from Manila to Vancouver in late September, early October, 1945, with a stop off at Pearl Harbour, Honolulu, to allow the American servicemen to disembark before their final, separate, sea leg home. The photo-card bears a ‘Good Luck’ message and I presume copies were handed to the servicemen as they disembarked. The British survivors then journeyed across Canada by rail, with a variety of stop-offs en route. There is a picture postcard of the Red Cross Reception Centre in Calgary, Alberta, and a small printed card welcoming the ‘Gallant defenders of Hong Kong. Manitoba Salutes You’, which seems to have been distributed in Winnipeg. Once again, I presume they were small mementoes my father felt worthy of preservation.

A more surprising series of mementos, to my mind, at least, is featured on a further photograph at the end of this blog. The photograph contains three unwritten postcards and some Japanese currency. I suppose we would call them souvenirs, and that is why I find their presence in my father’s ‘archive’ a little unexpected. Other items speak of captivity, camaraderie, endurance and strength, whereas these – well, I’m not sure what they represent . . . One of the cards is an artist’s depiction of a bustling open air market, somewhere in the Tropics. Clearly, something my father acquired during the weeks awaiting repatriation from the Pacific. One is an image, again the work of an artist, showing a small, intimate Christian religious service, and the third, the most puzzling of all, is a card depicting a stylised image of, perhaps, a Samurai-type figure. All three cards, are, despite the passage of time, brightly colourful compared to so many of the items in dad’s collection. But their significance is lost to me now. There is also a little Japanese currency. A handful of tiny, highly decorated notes. I recall being allowed to hold them when I was a small child! I might have even been allowed to use similar notes as ‘swaps’ with schoolmates when I was a little older and exhibited a month or two’s interest in coin collecting! My memory is not clear on that. I noticed only recently that one note had a faint message written on it to my dad from one of his comrades during the years of captivity.

An item not featured among the photographs shown in the blog is a post-war ‘Port Record Book’ issued in Grimsby in May, 1947. The war ended in the Far East in August, 1945. My father was officially demobbed – released from the armed services – in May, 1946, after a lengthy, recuperative, return journey back to Britain. The Grimsby document lists the two trawlers my father worked on during a brief spell as a trainee deckhand on the North Sea fishing fleet. He had no previous links with the East Coast or the deep-sea fishing industry. I recall the odd conversation with him about that and he seemed as nonplussed by his own decision to have given it a try as I was. If there was an industry designed to test ones nerve and fortitude at the time, it was certainly life on the trawlers. It took him up to the Icelandic fishing grounds and he recalled the job of ridding the deck and rigging of any build-up of ice that could capsize the vessels. It was a dangerous environment. The experiment lasted a few weeks. I often wonder if the captivity and frustration of the war years had prompted him to test himself in such an unforgiving environment?

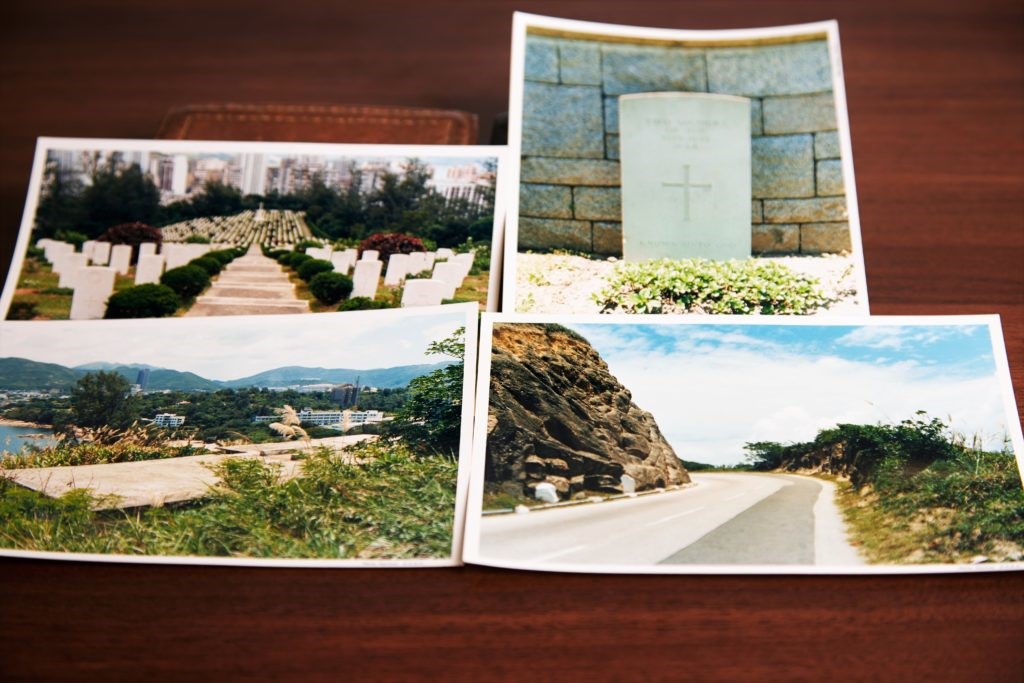

And finally, I’ll comment on another aspect of the ‘archive’ that I have a little more knowledge of than some other items. There’s a photograph included in those below featuring scenes of a war cemetery and headstones. In the 1980s my father contacted the authorities in Hong Kong in an attempt to reach some resolution with a matter that had clearly weighed on his mind since his war service. Seemingly, either in the final, confused days and hours of the defence of the colony in December, 1941, or after the official surrender, my dad and some comrades hastily buried two men who had fallen by their side in the fighting around Stanley Village. I think that although he had no idea of the combatants’ identities, he might have been aware of their military units, as men became separated and units became mixed. He provided the authorities with as much detail as he possessed, including hand-drawn maps and plans of the graves’ whereabouts. He was relieved later to receive the photographs illustrating the care and attention that had been taken in the intervening years to rebury the fallen and mark their roadside graves.

POSTSCRIPT

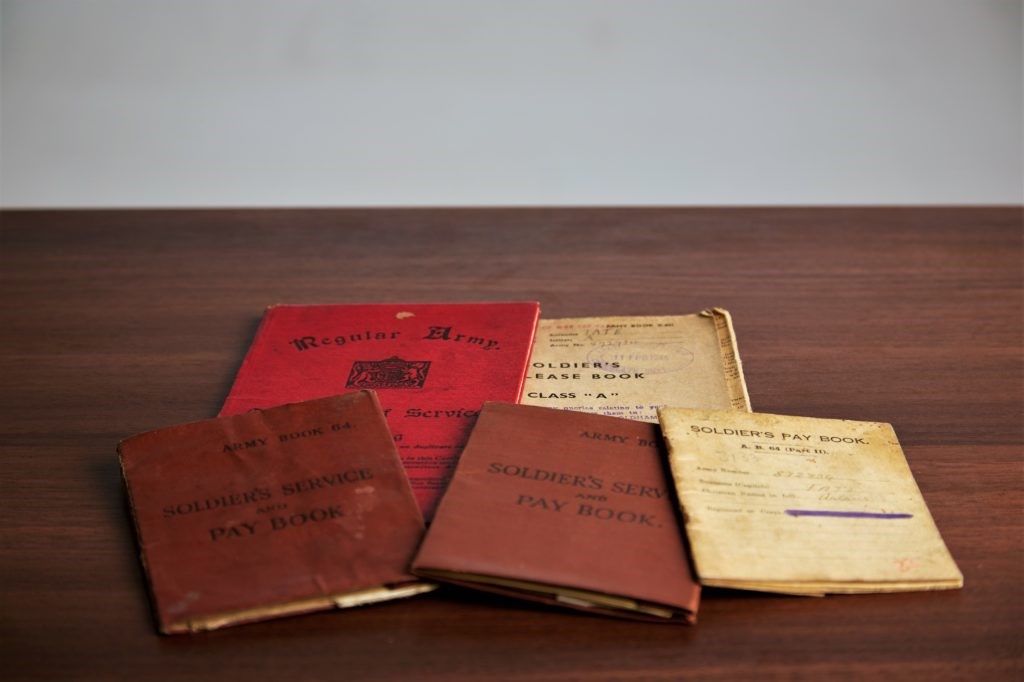

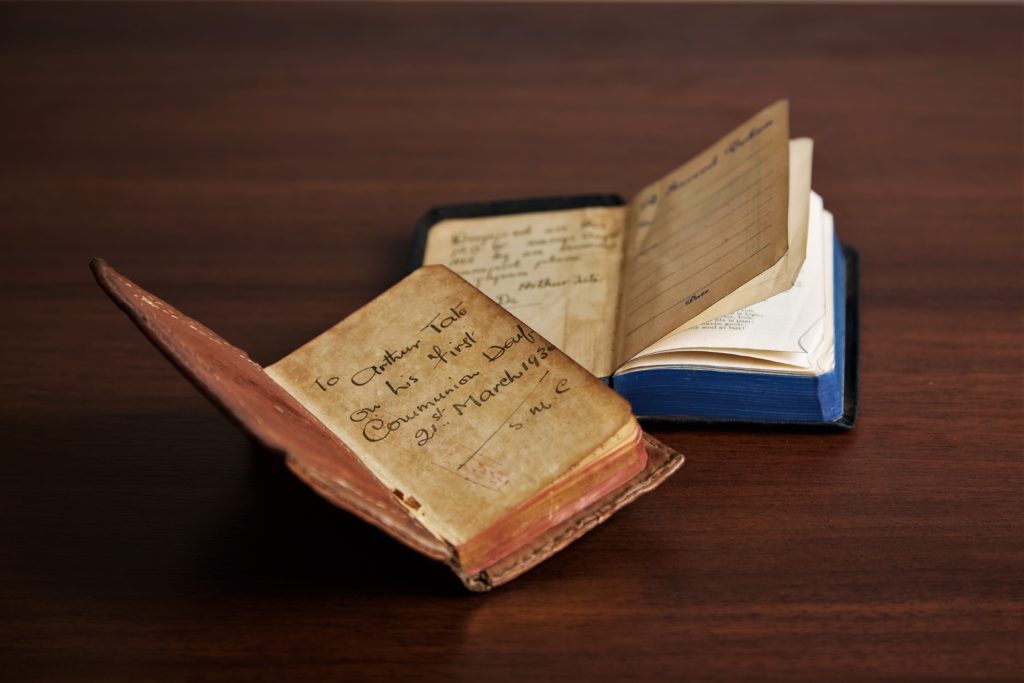

I thought I knew the nature of the material my father held close for all those years after the war. Not its full significance and context, but at least what it consisted of. But in examining the items again for this blog I was surprised to find ‘hidden’ in a small, fragile Service and Pay Book, that he had carried with him throughout captivity, a poem . . .

It had been written in pencil in tiny letters on a blank page of the Army-issue pocket book. But either time had rendered the script almost invisible, or it had been written so lightly as to deliberately escape detection at first glance. The paper is not torn or rough, and so I don’t think there was an attempt to rub out the text at some later date. The fact the book had accompanied my father on his Far East journey, and was not a later replacement provided as part of the demob process, is attested to by further handwritten notes, much clearer, at the start and end of the record book noting his stay in prison camps and the declaration, ‘War Over August 15th’, on the last page. The official details written in the book do not show the signs of intense fading exhibited by the poem.

It proved immensely difficult to decipher the writing even after I had spotted its presence, with only a few words here and there clear enough to make out. But with the aid of internet searches I discovered the poem, The Burial of Sir John Moore after Corunna. It is a eulogy to military sacrifice, camaraderie and honour. Of unity in the face of defeat. It speaks of British militarism. Of stirring fortitude designed to capture a boy’s imagination. Its author was Charles Wolfe. Occasional words of the eight-verse epic can be made out.

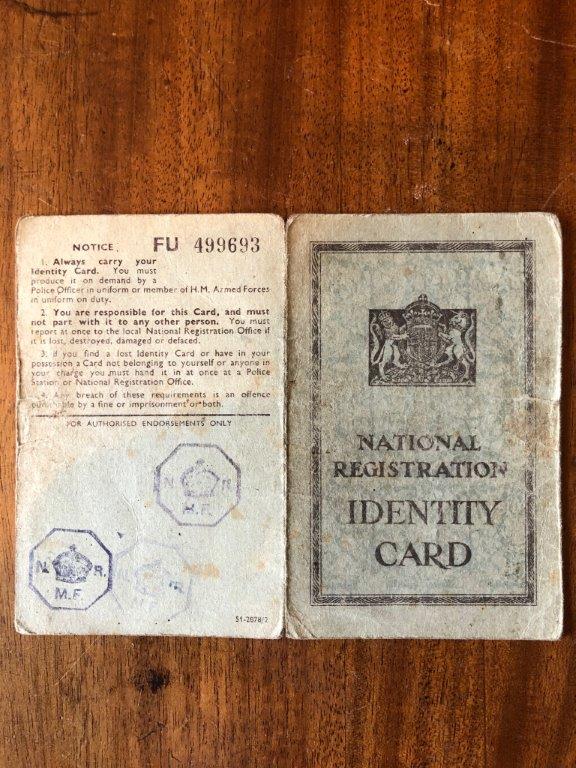

Remember, my father was just 15 when he lied about his age to join up in Blackburn in 1937 when he would have first been issued with the pay book. His ‘false’ date of birth is written clearly. He was a product of elementary schooling for the working classes where learning by rote and recitation was a central element of the mass education curriculum, especially of poetry which extolled Britain’s perceived place in the world order and which gloried in tales of Empire.

The poem, penned in 1817, resonates with an air of triumphalism over a ‘defensive victory’ at the Battle of Corunna in Spain, part of the Napoleonic Wars, as British forces retreated to the coast and evacuated under fire, with the commanding general Sir John Moore killed in action and buried by the port’s ramparts. I had never come across the poem before and I doubt it features much these days in any review of nineteenth-century poetry, although it was a staple of earlier popular anthologies. To modern ears it will jar with militaristic and colonial-era rhetoric and imagery. The honouring of an elite soldier while the rank and file dead were thrown in pits, with commemoration of the masses awaiting later conflicts. Its style, too, will appear laboured and formatted. But to impose our own world view or standards on what earlier generations thought appropriate, acceptable, worthwhile or entertaining is to do a great injustice to the past. We may not approve, but we should at least try to understand.

Memorisation and recitation were the main points of popular poetry engagement for millions during much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. There was a belief that the system helped store up a treasure of ‘worthy’ literary ideas to be drawn upon in later life as comfort and guidance. Writing of the power of memorisation, John Henry Newman, theologian and poet, suggested in 1870: ‘Passages, which to a boy are but rhetorical commonplaces, neither better nor worse than a hundred others which any clever writer might supply, which he gets by heart and thinks very fine … at length come home to him, when long years have passed, and he has had experience of life, and pierce him, as if he had never know them before, with their sad earnestness and vivid exactness.’

I can only speculate here. But perhaps as a boy dad had been thrilled by the imagery in the poem. Perhaps the tone of sacrifice and camaraderie had made such an impression that he chose to keep it close during the challenging years of captivity. I like to think so. I like to think that it might have provided some sense of escape, perhaps some sense of meaning or context to what he was enduring. But that, as I say, is mere speculation. It is an idea no clearer than my puzzlement as to the manner of its composition – barely legible but, to a young man who had perhaps learned it by heart, easily read and safe from the risk of forgetting.

I have finished previous blogs with quotes on the nature of history. I end this final blog with The Burial of Sir John Moore after Corunna, by Charles Wolfe. The poem is designed to be read as to the rhythm of a drumbeat . . . a replacement for the missing military drum tattoo at the hasty burial.

Not a drum was heard, not a funeral note,

As his corpse to the rampart we hurried;

Not a soldier discharged his farewell shot

O’er the grave where our hero was buried.

We buried him darkly at dead of night,

The sods with our bayonets turning,

By the struggling moonbeam’s misty light

And the lantern dimly burning.

No useless coffin enclosed his breast,

Not in sheet or in shroud we wound him;

But he lay like a warrior taking his rest

With his martial cloak around him.

Few and short were the prayers we said,

And we spoke not a word of sorrow;

But we steadfastly gazed on the face that was dead,

And we bitterly thought of the morrow.

We thought, as we hollowed his narrow bed

And smoothed down his lonely pillow,

That the foe and the stranger would tread o’er his head,

And we far away on the billow!

Lightly they’ll talk of the spirit that’s gone,

And o’er his cold ashes upbraid him —

But little he’ll reck, if they let him sleep on

In the grave where a Briton has laid him.

But half of our heavy task was done

When the clock struck the hour for retiring;

And we heard the distant and random gun

That the foe was sullenly firing.

Slowly and sadly we laid him down,

From the field of his fame fresh and gory;

We carved not a line, and we raised not a stone,

But we left him alone with his glory!