Dr Stephen Tate – September, 2020

Welcome to the latest instalment of the blog, Lest We Forget. As part of the WWII East Lancashire Childhoods project the blog has been attempting to examine how family memorabilia combined with shared recollections can help foster a better understanding of the generation associated with World War Two. If you recall, I explained in the opening blog how my late father, Arthur, served in the Royal Artillery as a teenager. He was taken captive when Hong Kong fell to the Japanese Army on Christmas Day, 1941, and endured almost four years as a prisoner of war in the Far East, he and his comrades used as slave labour in Japan’s heavy industries. He had joined up in Blackburn in late 1937 claiming to have turned 18, the minimum age for recruitment, when, in fact, he was still 15 and six weeks short of his 16th birthday.

Since the last blog was posted online the country marked the ending of hostilities in the Far East – VJ Day – on August 15 with a number of 75th anniversary commemorative ceremonies. The one at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire attended by Prince Charles was particularly moving, with the service of remembrance broadcast live on TV. The 150-acre site is home to 25,000 trees among which sit 400 memorials highlighting, in dignified solemnity, a wide variety of organisations and events of national significance, among them a number recording the suffering and fortitude of Far East Prisoners of War.

I think it is important to make the point here that this is not the appropriate forum within which to develop the issue of the ill treatment of captives in the Far East in the Second World War, nor the devastating atomic bombing of Japanese cities which forced Emperor Hirohito and his military leaders to accept defeat in 1945. That is not the purpose of this blog series. But it is important to at least acknowledge its presence.

The inhuman treatment of prisoners of war and, indeed, civilians, was a sub text to the conversations illustrated in the series of correspondence I touch on below. It was the context around which parents and son spoke to each other in print, of what was left unsaid but which, for son was the grim reality of every day, and for parents was the subject of a growing awareness as the war developed and the long years dragged.

Neither is this the platform to discuss the issue of empire and colonialism – Britain’s presence, and the presence of its troops, in the far-flung corners of the world, and of the growing appetite for empire within Japan at the time. This country’s colonial past has rarely been more open to debate, and the place of Hong Kong in the great sweep of international relations is before our eyes seemingly nightly as the former colony faces up to Chinese government attempts to integrate it more fully within its own political order. They are debates for another time, another place . . .

This project provided a welcome opportunity to discuss how memory, oral history and family artefacts can combine to provide a powerful image of the past, foregrounding the ordinary and the everyday elements of life that, together with the grand narratives of national sacrifice, help tell Britain’s World War Two story. In addition, it was a means by which I could share, in a small way, my late father’s experience of conflict and its impact on his parents, through examining some of the fragile official documents, correspondence and personal ephemera that have survived the passing of the years and that stand testament to a time of crisis in their lives – a crisis mirrored the length and breadth of the country in family narratives of war.

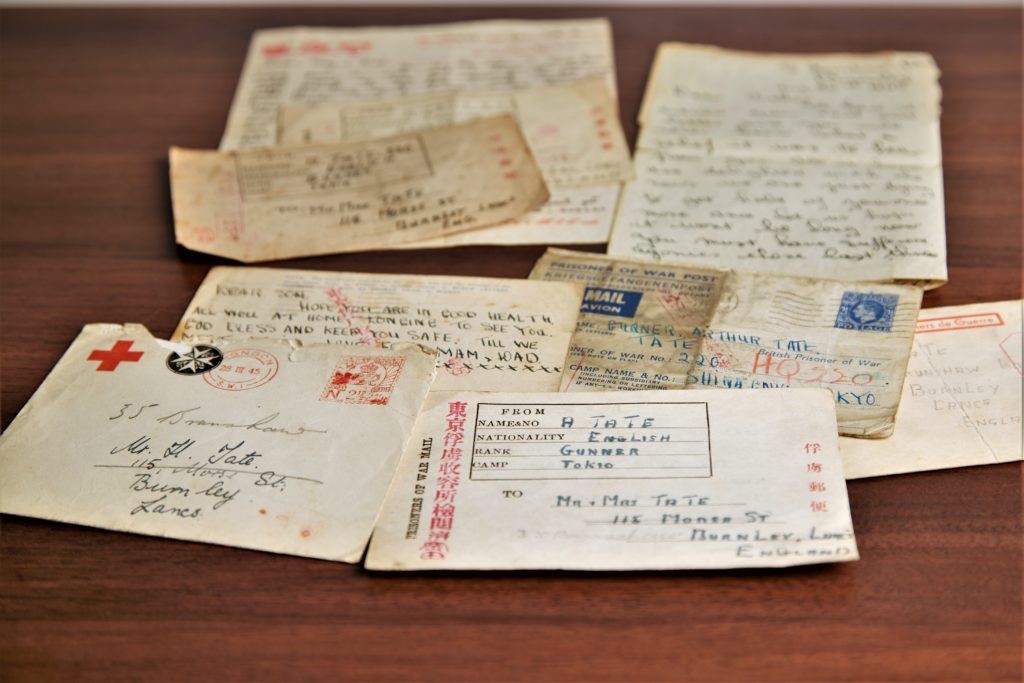

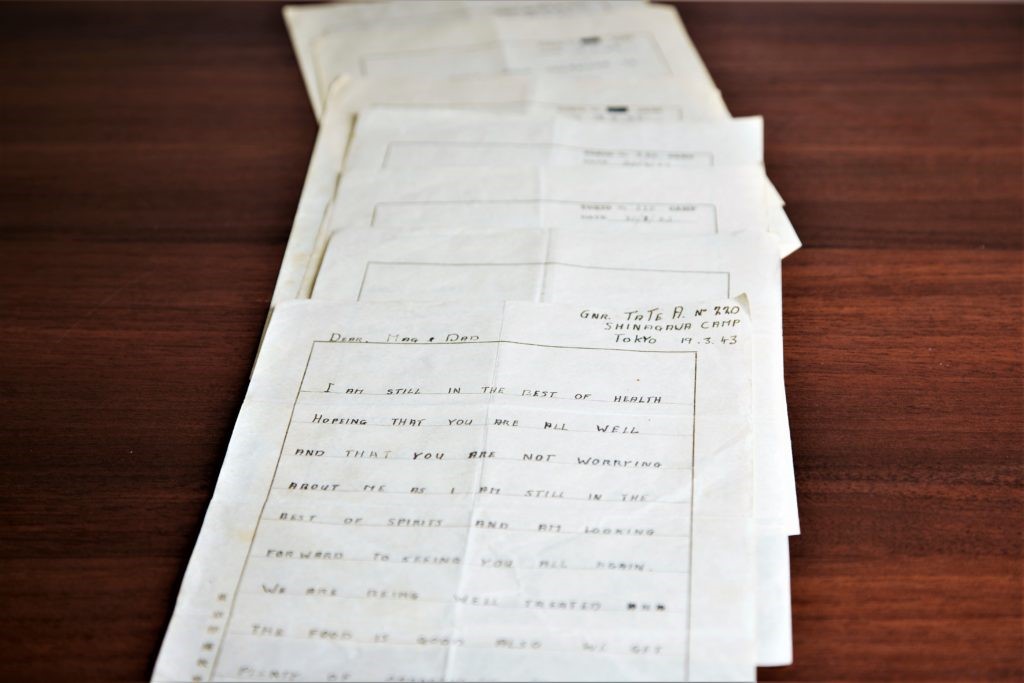

With this in mind, I turn to material that forms the bulk of my father’s ‘archive’ of imprisonment – very brief letters sent by his parents to their son in captivity and those they received from him. I have no way of knowing how complete the correspondence is. I never asked my father that question. But the messages are disjointed, not always a sense of one letter responding to another. Perhaps some are missing. It would be incredible, really, if they had all survived. And, no doubt, some never reached their intended recipient – lost, diverted, destroyed in the chaos of global warfare. There are more than a dozen items of correspondence – postcards, letters, telegrams – all showing signs of their age but surviving through a balance of serendipity and careful management. With each passing year the more I consider these fragile artefacts and the fact of their survival through warfare, the upheaval of freedom and then repatriation, together with the later bustle of civilian life . . . their presence seems ever more incredible . . . ever more precious.

The correspondence dates between spring 1943, to September, 1945. After the surrender of the colony at Christmas, 1941, my father had endured a prison camp on the Hong Kong mainland until being part of the first draft of Allied prisoners to be shipped out to the Japanese home islands in September, 1942. He survived transportation on what became known as “hellships”, merchant vessels requisitioned by the Japanese navy and overloaded with prisoners who faced dreadful conditions at sea. In Japan he had been held in three different prison camps, originally near Tokyo and later, I understand, in the far north of the country.

In one letter posted from a prison camp near Tokyo and received in East Lancs, I think, in May, 1943, my late father writes of not having had a letter from home yet – a year-and-a-half since captivity had begun for him. The anxiety created by that silence, for all concerned, dad in Japan, his parents in Burnley, must have been oppressive. Official lines of communication had only gradually been opened, and there’s a typewritten letter from the military authorities to my grandparents drawing attention to a Post Office leaflet explaining the means of sending letters to prisoners of war held in Japan. In all the correspondence sent by my father he makes the point that he is well, in good health, and being treated well. All patently untrue but included so as to increase the chances of the letters being forwarded from Japan and, importantly, to ease the distress he surely knew his captivity had created for family and friends. That May, 1943, letter appears to have been the first received by my grandparents. Their letter, in response, postmarked June that year – “The happiest day of all to know you were still alive . . . hope your pals are still with you to make things easier” – was not received by my father until March the following year, more than two years into his captivity! Clearly, others would have been sent but had not been handed on. The relief in my father’s letter home in response is clear – “. . . I cannot tell you how happy I was to find you all safe and well . . . am looking forward to seeing you all again hoping it will be soon . . . “.

The sequence of correspondence ended with the letter my father sent home to his parents in September, 1945, celebrating the war in the Far East ending and his release from the prison camps, which I mentioned in the second of these blogs.

Overall, the letters do not fit together seamlessly. They are disjointed, as are their contents. They reflect the time and conditions. There is no sign of censorship. I imagine the POWs were advised by senior officers as to what would be acceptable for the Japanese military to pass on, and those writing from Britain to the Far East would be equally circumspect over what they wrote.

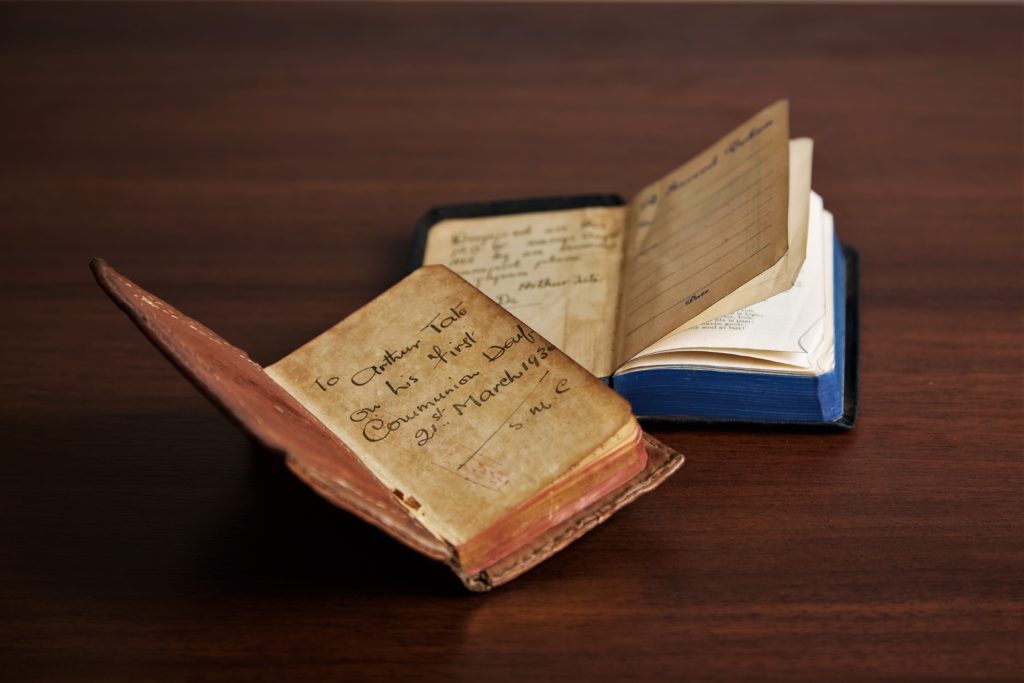

In addition to the letters mentioned above, there are two pocket-sized prayer books among my late father’s POW ‘archive’. Both are imbued with a tremendous sense of poignancy . . . One is a brown leather ‘Pocket Prayerbook’ with an inscription on the opening page – presented in boyhood to my father on his First Communion Day. It had stayed with him throughout his ordeal. Within it, in a neat hand, written in pencil are the names of 21 fellow prisoners of war with their home addresses – 17 British, three American and one Australian. Perhaps the intention had been to keep in touch after release. I don’t know if they did. But they had shared a harrowing experience. There is also a small blue leather New Testament. On the opening page my father had written in ink, ‘Dropped on this POW camp August 28th 1945 by an American Transport plane’, and he had signed it. The war had ended a fortnight earlier and the business of finding the camps and the Allied prisoners, of getting urgent food and medical supplies to them, often by air, and then preparing to send them home had begun. What emotions had gone through my father’s head as he wrote that short inscription?

In the fifth and final of these blogs I intend to examine the material my father saved relating to his end of captivity and journey back home to Lancashire, together with a remarkable discovery I made when looking at that material to refresh my memory in advance of writing these posts.

For those who want to know more about the plight of Far Eastern prisoners of war in World War Two, this link takes you to Captive Memories, a website containing research, and source material, conducted and gathered by the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. The material is based on the School’s 70-plus years of engagement with service veterans, their families and their histories. The School’s initial involvement centred on the veterans’ health problems associated with the effects of tropical infections together with the psychological impact of incarceration. There is a fascinating section on artwork by prisoners of war, done in secret at great risk. The exhibition – ‘Secret Art of Survival – Creativity and Ingenuity of British Far East Prisoners of War, 1942-1945’ – was staged at the Victoria Gallery and Museum, Liverpool, and is now online.

https://www.captivememories.org.uk/about

I have ended previous blogs with a quote from the writings of historians that, I think, have a resonance and worth in this current context, and which offer up insight surrounding the very idea of what History is. Today is no different, and the following is from an article by Dr Anna Whitlock, BBC History Magazine, October, 2015 – “The past is alive, dynamic, controversial and hugely relevant. History is constantly being written and rewritten, contested and reinterpreted. History is more than looking backwards and studying the past – it is about critically engaging with the present and the future. It is about individuals, families, nations and the global community.”